content warning: mentions of SA

When I first started reading One! Hundred! Demons by Lynda Barry, I knew instantly that it was going to be special. Perhaps it was the scrapbook-like art style, which drew my child self in like a moth to a flame. Perhaps it was the fact that Barry is half-Filipino–I was glad to read any kind of representation from my culture.

Now that I have finished this comic, I can confidently say that this comic is special not only for the reasons that I have previously stated, but also through its presentation as an autobiofictionalography, and what it implies about the representation of memory.

Lynda Barry represents memory as abstract, yet existing with nightmarish clarity. I use the word “nightmarish”, rather than “dream-like” in this context given that most of the memories presented in this text are evidently unhappy (hence why she associates each chapter with a ‘demon’).

Essentially, Barry asserts that we will remember the occurrence of an experience, as well as the feelings associated with this experience, but not how the experience actually happened.

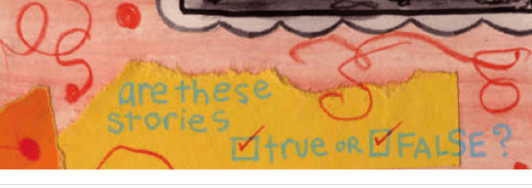

This theory is first proven by the below attachment on the Table of Contents page:

According to this ripped piece of paper, the stories presented in the text are both true and false. Thus, it would be right to assume that some aspects of the memories presented to the reader are fictional, wherein the ‘fictional’ parts try to make up for the gaps/the parts of the memories that cannot be remembered. In this context, the check-marked ‘truth’ here asserts the fact that these experiences happened. The check-marked ‘false’ refers to the fictionalization of how the experience actually happened in real life.

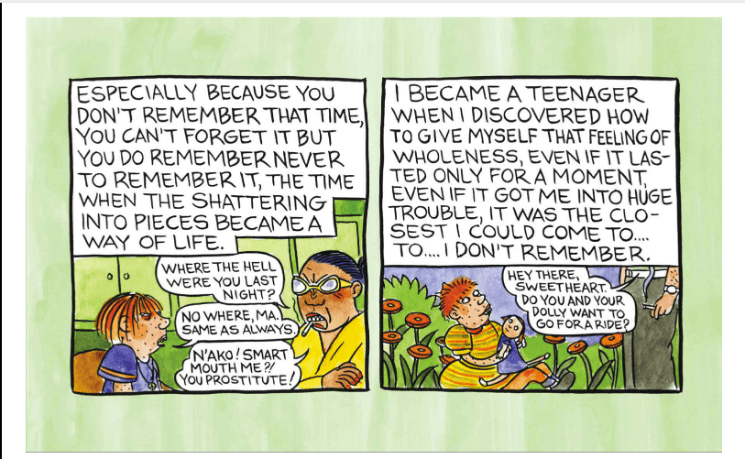

The last two panels in the chapter, “Resilience”, particularly show the complexity of truth, and the contradicting clarity and abstractness of memories:

In the first panel, Barry is speaking to her mother after returning home from a late outing. Whether the clothes they wore, the location they are speaking in (presumably the kitchen), and the exact dialogue is an exact depiction of the past is questionable. Regardless, Barry seems to recall at least one event in her life where her mother cruelly called her, a child, a ‘prostitute’. This event evidently remains with her as an unhappy memory. When juxtaposed with the following panel, this later memory in her life morphs into something even more awful.

In the second panel, there is a clearly younger version of Barry playing with her doll outside, looking up at a strange man. His intentions appear nefarious, asking a young girl to go on a ‘ride’ with him. Like the previous panel, it is likely that the interaction did not occur as exactly as it is depicted. Perhaps they were wearing different clothes, the location was different, and what the man said to her exactly was different. But when considering the following text, the true pain that Barry experienced becomes clear:

“I became a teenager when I discovered how to give myself that feeling of wholeness, even if it lasted only for a moment, even if it got me into huge trouble, it was the closest I could come to… to… I don’t remember”

-One! Hundred! Demons! Page 72

This text, overlaid with a background of a memory of implied sexual assault, shows that Barry remembers the trauma of her assault with unspoken clarity, even if she does not or cannot explicitly provide details of the cause of her trauma.

Thus, while how the memory happened can be questioned, the feelings, especially the pain associated with this traumatic memory is fact.